Irrational Rationality

Why do some people believe clearly false ideas?

It’s a question I’ve been turning over in my mind for… ah, no reason, really, just random thoughts, definitely not anything political. And since these random-but-clearly-not-political musings are bouncing around my head, I figured I could examine a couple non-politically charged ideas:

- QAnon? Nope, staying far away from that.

- Holocaust deniers? Hmm… no, if only because it turns my stomach.

- Chem trails? Meh… so last decade.

- Illuminati? So last century?

- Bill Gates seeding the world with metal snow? A little to far into the crazy.

- Flat Earthers? Ah, so I kind of feel like that one’s cheating.

Actually, let’s go with that: flat earthers. There are a not insignificant number of people that believe the earth is flat, truly. On the face of it, this is a remarkably obvious and to many, a stupid belief. There’s an astonishing amount of ‘proof’ that we live on a very large sphere called a planet. Not only are there clues to this on the ground, but if we just look up at the sky, we can see pretty much everything else out there also is a sphere. Then there’s all the videos and images from the international space station, satellites, the shuttle, etc, and it becomes pretty hard to believe that we’re living on anything but a spherical planet.

It might seem the only way to not believe the earth is a sphere is to dig a deep hole and bury yourself deeply within it. Yet I guarantee they’ve seen it all.

Give them this proof; I dare you; see what happens. Because for every piece of proof you give them, they will have a well-thought out rebuttal that ‘proves’ the proof is either wrong or has been faked. They will form a consistent, if somewhat elaborate chain of theories that each sustain the other. They will question your assumptions of where your knowledge came from and how you can be sure of it (can you truly trust anything from the media or the government?). They will pull from a deep well of alternative evidence and string the pieces together in an elaborate tapestry that just might have you doubting whether the very foundation of truth itself.

They do, in other words, exactly what we do. Their evidence will look like ours and sound like ours and even feel rational and sane 1, as though it were possible that any prevailing mass opinion of truth could actually be wrong. They will point out that humanity has often been wrong.

They’re not wrong.

Humanity has often been wrong. We all once thought the world was flat and all the heaven’s circled us, the very center of the universe. When you look over the course of history, you’ll find all sorts of peculiar beliefs embedded so deeply into the society of the time that it might as well have been truth for all that it shaped people’s lives. Even in the present day, you simply need to move a little outside of your community to find alien ideas entrenched in strange cultures, all held just as deeply as our own. They are foreign and clearly wrong, perhaps even a little childish, but behind them all you will find the same kind of rationality, of logic and experience combined with unshakable belief, that comprises our own closely held truths.

This becomes much more pernicious when you pit a deeply defended belief against prevailing public fact. Because prevailing public facts aren’t really thought about much. We don’t spend a whole lot of time wondering whether the world is flat or round. We’ve been provided the evidence, given the rational behind it, and let’s be honest: for that vast majority of us, it really doesn’t matter does it? Round or flat doesn’t change anything about our day to day life. We don’t need to build hard proofs for why it’s true and we don’t have the time anyway. We’ve life to live and only so much time to do it in.

Yet doubt digs at the back of the mind. What if we’re wrong? And why is it that people who are clearly wrong can be so convinced otherwise. How is it that they have so much proof, and why does it look just like ours?

Surely there must be some way to tell?

Perhaps. Perhaps not.

The problem is, all rationality is built on the tip of an ice burg of assumptions. As I’ve mentioned before, all logic is true, but only categorically. The moment you apply it to the world, logic looses it’s ‘truthiness’. The very process of applying logic to reality necessitates this. Reality is otherwise too big, too messy, too complex. Trying to question all our assumptions would only lead to paralysis; we simply don’t have the time.

Let’s take an example. By day, I’m a software engineer. As a software engineer, I’m often tasked with producing software dreamt up by people who do not write software. Some clients don’t understand at all why software takes so long, or how it’s possible to have a bug 2, or why some feature will take so long, or why it can’t be done at all. If software is just telling the computer what to do, then if the computer has done something wrong, it’s because you told it wrong.

Well…

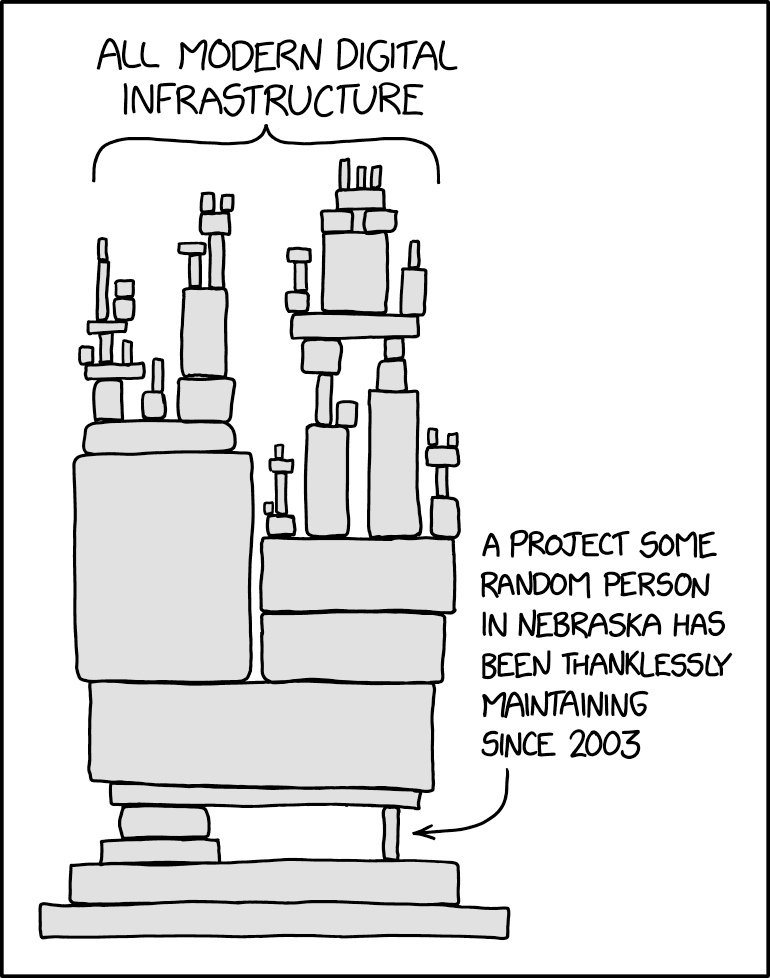

Software, like knowledge, is built on an absurd number of assumptions, except in software development we call these ‘dependencies’. We can’t build modern day software without them 3, but within those dependencies are hidden bugs, wrong assumptions, bad code, and poorly communicated interfaces. Even worse, software developers (being people), don’t often agree on the best way to do things. So some dependencies don’t work with others or do so poorly or cause your app to crash in the weirdest place. And because this is all happening deep within the dependency stack, it would take weeks of effort to comb through thousands of dependencies built with millions of lines of code. So we don’t. Instead, we hack a solution around the problem and plant a flag that says “Here be dragons; enter and die.”

This is why we can’t know the truth and why people believe lies. It’s not that truth isn’t a knowable thing, it’s just buried so deep within a million assumptions of life that to truly dive down and tease apart with logic and rational thinking would take the rest of our lives… or more.

I recently read an interesting article in Wired about quantum physics and causality. Specifically, some scientists are starting to believe that the effect of a thing could actually occur before the cause of it. This, of course, is absurd. A cause must precede an effect… except maybe it doesn’t. We’ve already learned from quantum experiments some things can be more than one thing at a time occupying more than once place at a time. Recent experiments suggest time and causality itself also may not behave in the way we’ve always assumed.

Put another way, we’re realizing that to understand our world better, we must break some of the most foundational assumptions of how we believe the world works.

Will there come a day when our very conception of causality will be looked upon as childish and simple, the way we now look on those who believe the earth is flat? Will there one day be a contingent of theorists consummately amassing an army of evidence to restore the faith in such an outmoded way of thinking?

All of our carefully constructed evidence, rationality, and logic will always look the same, no matter how true it is. Building more evidence or constructing more logic won’t make it any more or less true. Perhaps rationality and logic was never intended 4 to ‘know the truth’. Perhaps it is, at most, a tool, a functional piece of our mind that stitches together our experiences into a seamless narrative with duck tape, glue, and false assumptions. Yet it’s an effective tool that conjures the illusion of a seamless whole that looks and feels real because it works.

And perhaps that’s all we can ever expect from our minds. We want to have the certainty that we have grasped the truth itself, but perhaps all we’ve ever grasped was something effective. Never mind that lots of people believe lots of different things just as passionately as us, and with all the same kind of logical evidence backing them. Never mind their views of the world can work just as well as ours and sometimes even better.

Perhaps the most rational thing to do is eschew rationality, accept as true what we must to live, and plant in all the cracks of our ideas flags that say: “Here be dragons; enter and die.”

-

At least in that singular moment before you stick you head up for air and bathe once again in the prevailing opinion of the masses. You will then breathe easily, snug and secure in the knowledge that everyone around you actually agrees with you. ↩

-

Because surely a bug means the developer has made a mistake and why should I pay for your mistakes? No kidding, I’ve had clients tell me this before. ↩

-

Okay, technically we can, maybe. It would just take an absurd amount of time. We’d either have to start from the beginning and rebuild several decades of computer science, only to make an app/program that probably has more bugs than the dependencies we eschewed because those dependencies came from thousands of people smarter us working far more hours than he have available in our lifetime. ↩

-

Whether by God or evolution or both or aliens, I will not comment. ↩