Instrument of Omens

by: David Ashura

Somewhere in the preface to the first book, David mentions that his source of inspiration revolves around greats like Tolkien and Jordan. I usually roll my eyes when I read something like this, not because Tolkien and Jordan didn’t write great books, but that naming them as inspiration is so often done it’s become something of a trope at this point. They practically defined entire genres of fiction. Of course you took inspiration from these source, who hasn’t?

But it did get me thinking. The Lord of the Rings and The Wheel of Time are both massive works, and in this way they are something like the Bible: two different people can take very different, if not diametrically opposed, interpretations of it. It is no surprise that many books inspired by these greats can so often look nothing like each other.

So what does David Ashura think makes those works great? How did he weave those elements into his books?

More importantly, what can I learn from this?

Note: Spoilers, maybe? I’m gonna discuss some plot elements I do not really consider spoilers, but some might. There will be serious spoilers for TLOTR and WOT, though. Reader beware.

Cinder Shade wakes up face down in a well. No, scratch that. Cinder Shade dies, then he wakes up face down in a well. This all happens in the prologue and first chapter, setting the stage for the book. And already we have our first element:

The Chosen One

It’s a really common trope, but it’s an attractive one. Who doesn’t want to have a destiny, to discover themselves the hero in some grand story 1? In this case, David starts the story with a mysterious protagonist that doesn’t remember their past and is so obviously someone else. We’re immediately drawn in to the mystery of who might this character be as he demonstrates powers and skills 2 and knowledge and wisdom far beyond his years.

At least until chapter 4, maybe, when someone whispers to someone else about some sacred hero who’s destined to return 3 and oh but dear, whatever could that mean?

And yes, Rand al’Thor is the Dragon Reborn and Frodo will deliver the ring to the flames of Mount Doom and save the world. It’s the same story, recycled over and over, and yet we still read it because we’re all addicted to the idea of being the chosen one.

David Ashura does not disappoint in this. Our protagonist is indeed the chosen one, and he will save the world 4, and if you’ve read David Ashura’s other series, you do, in fact, know exactly who our character really is.

There is nothing new here. There’s no real twist or even a re-imagining of the trope. It’s just the trope, thank you very much, and please hold the spice. Does this sound like a criticism? Cause it’s not. It takes real talent and skill to understand a trope well enough to distill it down to its essence and manage to write a story with it that is still interesting and enjoyable.

This will become a theme with David’s writing: There’s nothing new here, but what is here is good, and enjoyable, and we still read it because David is a good writer and knows what he’s doing.

Power Progression

I’ve mentioned power progression before so I won’t belabor the point here. We like seeing our protagonist overcome odds and gain power. The “what will he do/learn next” is a powerful addictive, enough to keep the pages turning as our protagonist moves from school to school, always starting at the very bottom and yet somehow ending up first in class against all odds while he acquires powers “his kind” should never have.

And now I’ve ruined almost the entire first book.

You’ll still read it though, cause if you like power progression you already knew how the story ends. You’re not reading it to find out anything you don’t already know. You’re reading it for the fantasy of the journey itself and, probably, you close your eyes with dreams of yourself in our protagonist’s proverbial shoes.

The underdog that isn’t really

It’s usually tied to power progression, but I think it deserves it’s own element. We like underdogs, we like seeing them succeed, and we like seeing arrogance brought low and our bullies wallowing in the mud. And so the protagonist is cast as the underdog even though he’s the chosen one, while the book brings on the stereotypical, two-dimensional bullies that are really only there to reaffirm that bad people are only bad because they are bad people.

Sigh.

I will give David this: while every bully starts out pretty much the same, he does try to flesh them out over time. I will be honest, though, in that it felt like little more than sleight of hand. While the bullies do end up seeing the error of their ways, so often what really happens is they come to accept our protagonist’s actual greatness cause what else could they do when he’s showing them up so damn thoroughly?

But the only reason the bully is a bully is because they believe their superiority entitles them to be so. And so the only possible solution is to “put them in their place.” Show them they’re not superior, you are.

There’s no exploration of the human side of being a bully and that is always a disappointment to me.

Our world-threatening evil

It’s evil, and it threatens to destroy the world, maybe even all of reality.

And that’s all you need to know. Just like the bully, evil is because it is evil. All you really need to know is that it must be destroyed and it’s only weakness is in its propensity to monologue its plans to anyone willing to listen. Perhaps there’s a reason; perhaps the evil had been offended by someone; perhaps someone died ten thousand years ago and the evil is still trying to burn the world down over the injustice; perhaps the evil is just insane. Does it really matter, though? It’s evil, and any other justification for its deeds are merely side dressings.

In this, the endless slog of paper bullies provide a more meaningful dread.

The Prince | Princess Trap

I… don’t think Tolkien or Jordan ever really integrated this element into their stories. Frodo, certainly, had no forbidden love with royalty and Rand sort of did, but then that was more like a harem and so does it really count?

Either way, forbidden love is a common trope and when that love is a forbidden princess (and foreordained on top), there’s plenty of tension for the author to play with. And he does, and it’s good writing. It also breaks up all the school scenes in a satisfying build up.

A trope it may be, but it’s one I wish more authors would use. I hate harems and too often true love comes across as little more than hormone-ridden teenage angst, which I admit is not something I find pleasant reading.

My biggest issue is when the entire point of the princess is the hero, like, that’s her reason for existing at all. It’s subtly but deeply misogynistic (or misandristic… 5), and David tries to avoid it by fleshing out the princess as a person the best he can. The subtlety creeps in during those fleshing-out scenes, when you realize the entire point of them is still our hero.

To be fair, this isn’t just the princess problem. She’s not the only one who’s only thinking about our hero; everyone else is too. All of reality, it seems, watches eagerly for what they will do next. This is to be expected to a certain degree; the book is about our hero, after all. The problem arises when you never catch a glimpse of people living their lives outside of our hero’s warm glow.

David does not veer to egregiously into this, and he does do a lot to try to flesh out some of the other characters, but there did come a point where I started to feel as though I’d arrived in an uncanny valley where everyone’s attention was trained solely on the hero.

Racial Tension

David has a history of trying to address racism, although he tends to depict it in a decidedly un-American way 6. His “Uncastes” series literally has it in the title. In the “Instrument” series, the overt castes has been replaced by actual races: Elves, Dwarves, and Human, mostly. This sets the stage for most of the bullying seen in the book. The Elves are superior, and they have an unhealthy obsession with bullying the weakling human race because… they can? I never quite figured out why.

The tension between the races drives a whole lot of the plot, and it feeds right into the underdog/bullying element.

It also felt thin.

Does all racism boil down into a type of bullying? Is it racist to take a whole race and depict them as racist bullies?

David doesn’t quite go there as much as he starts there, and then works to flesh out individual characters. He first paints the broad strokes of a society dominated by their own chauvinistic tendencies, then pulls individual characters out of that culture and gives them depth as they begin to realize their mistakes.

On one hand, I like seeing characters change; I like seeing depth. On the other, the culture he paints feels flat to the point that the only thing any character can do to gain depth is to abandon the painting into which they were born.

A Greater Whole

David has, indeed, absconded with all sorts of primary elements from his inspired classics and used them wholesale in his stories. He’s done very little, if anything at all, to change them. There’s almost no twist or gotcha; there’s no reinventing the wheel; there’s no surprise here. They’re all rather ordinary, really.

What he does do, though, is weave together a bunch of common elements into a very good story. He doesn’t need to be original when he can turn standard parts into a greater whole. And despite my criticism of each element, I cannot criticize how he’s put them together.

I really enjoyed the books, and I’m quite looking forward to the next one in the series.

Just because something is common or ordinary doesn’t mean it isn’t good. It doesn’t mean it’s lost its draw. More importantly, you can tell David loves this stuff; he enjoys writing it. That comes out in his writing. He’s retelling a story you already know, but he loves this story and so do you, and you don’t care if you know it already, you just want to hear him tell it all over again.

Info

Author Website

Amazon Author Page

A Testament of Steel (Amazon)

A Testament of Steel (Author)

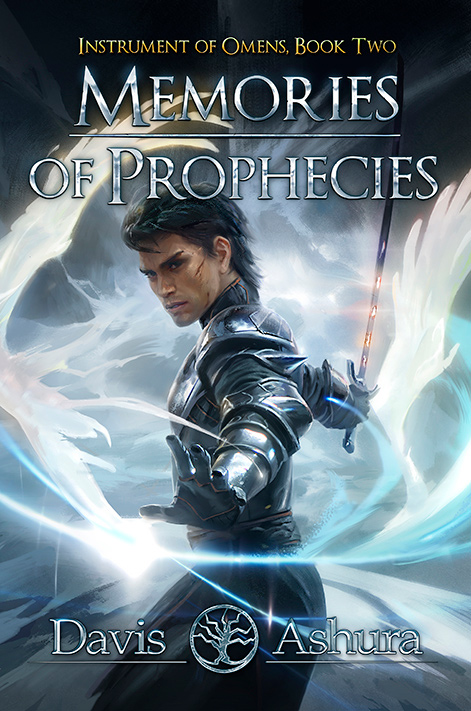

Memories of Prophecies (Amazon)

Memories of Prophecies (Author)

###

-

Me. I don’t. Really. Have you really thought about what it takes to be a hero, how miserable and absurd your life would be? Strip away the special effects and really look at the hero’s life. It’s shit. Who cares if you have all this power and saved the world, if in the end you’re miserable and possibly insane? The wisest thing Frodo could have done was to say “Fuck you,” to Gandalf and stayed in his happy valley. Let someone else throw a stupid ring into lava. I’m gonna grow some grapes, ferment them, and enjoy the view from here. ↩

-

or skillz. ↩

-

Nod nod. Wink wink. ↩

-

I presume. The series isn’t finished. I might like to see the hero fail, the world to end, and the multiverse to shrug and move on. ↩

-

So, misogynistic describes someone deeply prejudiced against women, misandry (misandristic?) is someone who’s prejudiced against men, but what is a gender neutral word that describes someone who is prejudiced against anyone not of their sex (including orientation)? You could use sexist, but that term is heavily loaded, frequently used as an insult or curse, and tends to be used to describe men (if someone is sexist, you almost always assume they’re male). I am annoyed there isn’t a more neutral term that can apply equally to anyone. ↩

-

We don’t have a caste system in America, and it’s deeply offensive to even suggest something so obtuse. No, we prefer to dress up our racism in the practicality of law so that we don’t have to notice it’s there. That way we can pretend equal opportunity and quickly lay blame on those who don’t rise to the top on their own laziness and/or inherently inferior culture. ↩